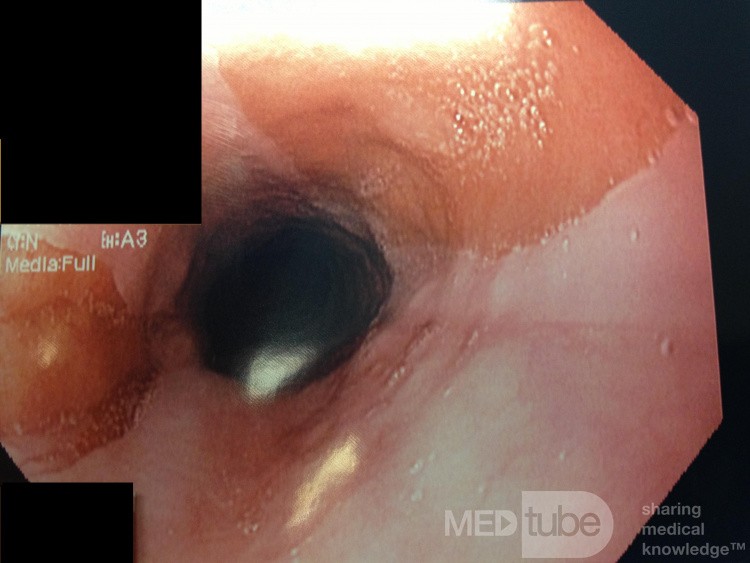

Ectopic Gastric Mucosa (Inlet Patch)

Case description

Path report showed "fragments of chronically inflamed gastric and gastroesophageal mucosa along with a fragment of benign squamous mucosa with mild congestion. The gastric mucosa is oxyntic mucosa. There is no evidence of ulceration of malignancy. Changes are suggestive of gastric heterotopia."

Information about Inlet Patches taken from UpToDate is below:

Inlet patch — An esophageal inlet patch (also referred to as heterotopic gastric mucosa of the upper esophagus [HGMUE]) consists of a discreet area resembling gastric mucosa that is typically found in the proximal esophagus. The prevalence of the inlet patch in the general population approached 5 percent in an autopsy series [48], while endoscopic studies have reported it to be present in 0.4 to 11 percent of patients undergoing diagnostic upper endoscopy [61-68]. The lower prevalence in endoscopic studies may be due to the proximal location of inlet patches. They are most commonly found in the proximal 3 cm of the esophagus, usually just distal to the upper esophageal sphincter, an area that is not always seen well during routine upper endoscopy [61,63,65]. Inlet patches have been described in people of all ages, but the most common age of detection is in the mid fifties [66].

Pathogenesis — The pathogenesis of the esophageal inlet patch is not known precisely. The term "heterotopic" gastric mucosa, sometimes used to describe it, may be a misnomer since some evidence suggests that the patch is composed of embryonic (rather than heterotopic) gastric mucosa. Immunohistochemical analysis has shown that the patch contains glucagon reactive cells that are not found in the mature human stomach, but are seen in its embryonic form [69]. In addition, the patch is frequently discovered in children and its prevalence does not increase with age [61,62].

One hypothesis is that the columnar lining of the esophagus in the embryo is not completely replaced by pseudostratified squamous epithelium during fetal development [70]. However, conflicting data have also been published. Some studies based on immunohistochemical analysis found that inlet patches more closely resemble Barrett's mucosa, an acquired lesion, rather than normal gastric mucosa, making a congenital origin seem less likely [71].

Several authors have advanced a "mixed theory," suggesting that the patch occurs as the result of a loss of normal squamous epithelium (from trauma, regurgitation, or infection) and subsequent healing by surfacing ectopic gastric mucosa present in the underlying lamina propria as the result of a congenital anomaly [71-73].

Clinical features — The patches range in size from 2 mm to 4.5 cm and can be solitary or multiple [62,64]. They are usually red, velvety, and flat (picture 5), although raised polypoid patches have been described [74].

Biopsies reveal corpus or fundic-type gastric mucosa [61,63,64,66], sometimes with parietal cells capable of secreting acid [67,75,76]. Microscopically, inlet patches also commonly have an associated inflammatory infiltrate [62].

Most inlet patches are found incidentally and do not cause symptoms. In a prospective study, an inlet patch was found in 11 percent of the 300 studied patients, but there was no association between the presence of an inlet patch and the reported severity of pyrosis, hoarseness, or dysphagia [68]. However, a wide range of clinical sequelae have been attributed to inlet patches, including:

■Perforation and a tracheoesophageal fistula occurring at the site of an inlet patch [77,78]. The presumed mechanism is related to acid production by the patch.

■Dysphagia, commonly from strictures, rings, and webs associated with the patch [79-81]. The association with webs and the potential for acid production and ulceration has led some authors to propose that the inlet patch is a possible underlying etiology for Plummer-Vinson syndrome [82]. (See "Esophageal webs and rings".)

■Interestingly, Helicobacter pylori can be localized in the patch in 19 to 73 percent of patients who are colonized in the stomach, raising the possibility that it acts as a reservoir for oral-oral transmission [64,83,84]. In a study with 68 patients with inlet patches, H. pylori was detected in 23 percent, all of whom reported globus sensation, suggesting a possible correlation [85]. (See "Globus sensation".)

■Some studies have found that up to 20 percent of patients with an inlet patch have concomitant Barrett's esophagus in the distal esophagus [66], but others have not confirmed such a correlation [62].

■There are numerous reports of esophageal adenocarcinoma arising from an inlet patch in the upper esophagus [86-88]. Additionally, there is one report of laryngeal adenocarcinoma diagnosed in a 22-year-old with an inlet patch [89].

■An association with globus sensation, chronic cough, and laryngopharyngeal reflux has been suggested in various reports [90-93]. A small randomized, sham-controlled trial found improvement in globus symptoms after ablation of the patch with argon plasma coagulation [94]. Thus, it may be reasonable to look for inlet patches in these patients and, if found, attempt ablation with argon plasma coagulation, multipolar electrocoagulation, or radiofrequency ablation. (See "Globus sensation".)

Diagnosis — Diagnosis

Other photos of this user

Serrated adenoma

American Association for Primary Ca…

views: 4531

Serrated Adenoma

American Association for Primary Ca…

views: 5925

Recommended

Portal Venous Gas

Noll Jan-Philip

views: 530

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Armando Hasudungan

views: 952

Multiple Stone CBD ERCP Clearance

Adrian Wróżek

views: 902